Deb Sokolow: Profiles in Leadership // Drawings without words

The Brooklyn Rail

by Elizabeth Buhe

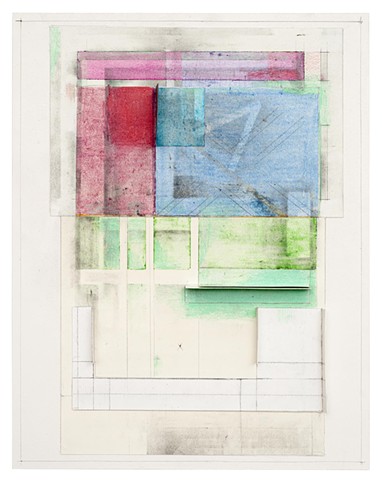

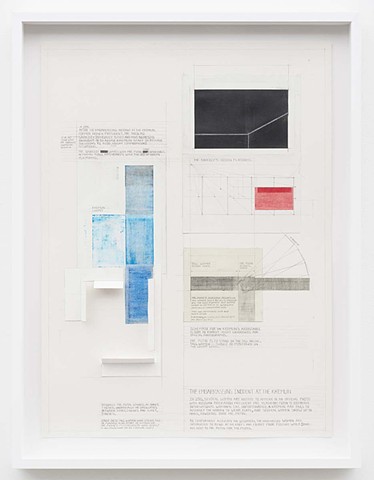

December 2019The two bodies of work on paper (all 2019) by Deb Sokolow currently on view at Western Exhibitions share much in formal terms: they are structured by scaffoldings of precise graphite lines that bolster transparent drawn boxes and collaged patches of smudgy color. The “Profiles in Leadership” series, which expounds on bizarre moments in the lives of powerful men, Kim Jong-Un, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Ronald Reagan among them, also includes blocks of text meticulously hand drawn in all caps. Sokolow is well known for the humorous jabs at authority these texts shuttle in, but that very function is evacuated in “Drawings without words,” the other series on view in this exhibition, the artist’s fourth solo showing. As the name of this second series suggests, these are works that include no writing at all. Taken together, the two bodies of work picture the systems that hold information in place and around which we negotiate everything else: our truths, our histories, our bodies, and so on.

From anecdotes relayed in “Profiles in Leadership,” we learn, among other things, that David Copperfield has been employed by a political campaign to disappear candidates about to commit verbal self-sabotage, that Vladimir Putin has prepared muffins from the flesh of a shark he single handedly overpowered, and that Fidel Castro categorically evaded women to avoid being poisoned. Penned in the present tense, Sokolow’s (his)stories are enlivened and made available for reimagining, a task which she approaches with apparent glee. While the texts clearly transpose fact and fiction, what is more interesting than parsing truth from deceit is the suggestion that these categories are always already unstable and freighted with bias. It is, after all, largely the history of victors that we have inherited, making Sokolow’s fabulations function as a kind of critical intervention. Mr. Richard Nixon’s Difficulties with Ovals, Version 2 describes the former president’s suspicion of oval rooms in the White House, which he believed were responsible for his path toward impeachment and emitted an “unseemly amount of expressive feminine energy.” As Nixon paces back and forth, the ovals follow him, inducing paranoia. While surrounded by architectural and textual systems that secure power, we see the very authority these systems are constructed to valorize and fortify degraded by irrational fears of hysteria, poison, and grime. In exposing the human tendency to entertain mystical, subcultural, and sinister explanations—a tendency which extreme authority apparently does not render impotent, but actually exacerbates—Sokolow shoots the supposed genius of these men through with doubt.

In the second gallery, Sokolow withholds textual cues in If Madame Blavatsky Had Been an Architect and her other “Drawings without words.” In Madame Blavatsky, triangles, trapezoids, and elevation sketches in pinks, blacks, and emerald greens suggest the theosophist’s ostensible architectural creations. But even without narrative, the work retains Sokolow’s characteristic interrogation of authority. Power is not represented here in the form of a singular political or cultural figure, but as the weight of the history of abstraction. This is suggested by both Sokolow’s colored patches, reminiscent of the stained canvases of Washington DC-based color field painters like Sam Gilliam or Kenneth Noland, as well as the oft mysterious narratives that weave together politics and that tradition of painting. In earlier artworks, for instance, Sokolow has explicitly interrogated Noland’s links with John F. Kennedy and the murder of a woman believed to have carried on affairs with both the painter and the politician. By invoking abstraction in “Drawings without words,” she nods to its erstwhile, though deceptive, imperative for autonomy from the social, political, and, especially—given the departure from textual cues—the literary. These are perhaps the most beautifully chromatic works Sokolow has ever produced, with color seeming to compensate formally for text. Despite the vernal palette, however, there is a sense of melancholy here, as if these rooms—all the titles reference architecture—are inhospitable, uninhabitable, scrubbed clean. Yet in Sokolow’s abstractions there is also a sense of freedom: from the stories of powerful men, and from the critical labor of confounding their truths.

Elizabeth Buhe is a critic and art historian based in New York.

A New Contemporary Art Museum in Virginia Leads with Politics

Hyperallergic

by Amanda Dalla Villa Adams

April 24, 2018A New Contemporary Art Museum in Virginia Leads with Politics

AN ORGANISM IN RICHMOND: In the future we predict a large and significant living organism will begin to take shape at the corner of Belvidere and Broad … There are other organisms in Richmond, to be sure, but none quite like this one.

RICHMOND, Virginia — So writes Chicago-based artist Deb Sokolow in her pamphlet, “A Living Organism at Broad and Belvidere” (2017), commissioned for Declaration, the inaugural exhibition at Virginia Commonwealth University’s new Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) — located at the corner of Belvidere and Broad streets. The pamphlet, available for guests to take, sits in a bin next to one of the two entrances into the ICA. It serves as an introductory statement reflecting the hopeful anticipation of a university, philanthropists, and staff, but also a larger city and region of onlookers.

The long-awaited museum, whose first exhibition features 34 emerging, mid-career, and established artists (all living, save for Felix Gonzalez-Torres), has been approximately 15 years in the making. Construction of the building began in June 2014. On opening day, Saturday, April 21, the museum welcomed 6,000 visitors.

Changes in leadership notwithstanding — the curator list cites Chief Curator Stephanie Smith, former director Lisa Freiman, Assistant Curator Amber Esseiva, Curator of Education and Engagement Johanna Plummer, and former curator Lauren Ross — there remains a cohesive curatorial vision to Declaration. Perhaps this is because that vision is one of change, diversity, and socially-minded activism predicated on fluidity of interpretation and the elevation of marginalized voices. The exhibition’s fluidity is partially informed by the ICA’s building, which was designed by New York-based Steven Holl Architects and inspired by writer Jorge Borges’s concept of “forking time,” from his short story “The Garden of Forking Paths” (1941).

(continue at https://hyperallergic.com/439629/new-virginia-commonwealth-university-institute-contemporary-art-inaugural-exhibition-declaration/)

Hirshhorn Acquires Ragnar Kjartansson’s ‘Me and My Mother,’ Work by Shirin Neshat, Deb Sokolow

Artnews

by Nate Freeman

September 11, 2017(Excerpt)

The museum acquired in total 18 new works, including offerings by Hurvin Anderson, Aaron Garber-Maikovska, General Idea, Zhang Huan, Annette Lemieux, Shirin Neshat, Deb Sokolow, and Mika Tajima.

8 Comics to Read in October

Vulture

By Abraham Riesman

October 2, 2017The Best American Comics 2017 by various, edited by Bill Kartalopoulos and Ben Katchor (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Okay, okay, I suppose it’s cheating to put a best-of compilation on a best-of list, but this year’s Best American Comics is too good to pass up. It’s great from before it even begins in earnest — ever the Borges disciple, cartoonist Ben Katchor concocts four delightful fake documents about comics, including a harrowing pamphlet from the “National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Cartoonists” entitled “I Am a Cartoonist, Not a Mental Health Problem.” The creators protected by that society do quite well for themselves over the course of this volume. Luminaries such as Joe Sacco, Bill Griffith, and Ed Piskor are all in attendance, but pay attention to the work of the slightly lesser-known talents: the cheerful body horror of Ben Duncan, the medium-stretching abstraction of Deb Sokolow, the evocative diaries of Gabrielle Bell, the hard-core punk inks of Josh Bayer, and the charming crudity of Sienna Cittadino, just to name a few of the more memorable entrants.

Vanity, Thy Name Is Man

Hyperallergic

by John Yau

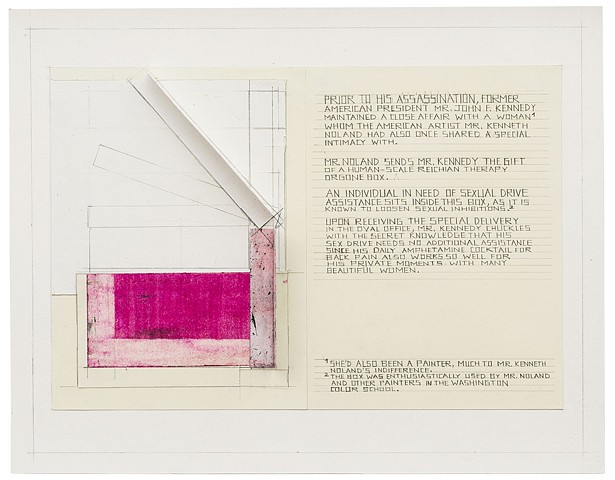

October 2, 2016CHICAGO — I was hooked by the time I finished reading “Mr. John F. Kennedy and Mr. Kenneth Noland” (2016), a text-filled drawing written in pencil in large and distinct capital letters that reminded me of penmanship practice in elementary school. In this work, presented in a shallow, simply made box resembling a maquette for a minimalist sculpture made from afar, Deb Sokolow connects Kennedy and Noland through Mary Meyer, who was the lover of both men, and who was murdered in October 1964, a crime that remains unsolved. However, instead of focusing on the woman (whom Sokolow never names), she creates a fiction based on Noland’s nine-year involvement with Reichian therapy, which promised to release inhibitions and improve the adherent’s relationship to sex and sexuality.

In Sokolow’s version, Noland gives Kennedy an orgone accumulator, a box-like object that Wilhelm Reich developed to help patients rid themselves of inhibiting factors, or what he called “armoring,” that prevented them from enjoying sex. The patient was to sit inside.

We are most likely meant to infer that Noland sends the orgone accumulator to help Kennedy with his sexual vigor as well as his many physical ailments, including his well-known back problems. However, as Sokolow writes in her last sentence:

Upon receiving the special delivery in the oval office, Mr. Kennedy chuckles with the secret knowledge that his sex drive needs no additional assistance since his daily amphetamine cocktail for back pain also works so well for his private moments with many beautiful women.

Sokolow divides her text into four separate sections, each a sentence long, with the capital letters neatly fitting inside the lined format she has drawn on cream-colored paper. The work’s appearance and content reminded me of the first few sentences in Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art:

1. Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.

2. Rational judgements repeat rational judgements.

3. Irrational judgements lead to new experience.

4. Formal art is essentially rational.

5. Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.

Sokolow’s first sentence is factual and forms the springboard for the artist’s carefully choreographed flight of fancy. Each subsequent sentence builds on the premises of the preceding one. Like a trapeze artist, she knows exactly when to let go of the bars in order to move on to others. They say that timing is everything, and Sokolow seems to be a master of it. She never goes too far, and never writes more than we need. What makes her pieces successful is their pitch-perfect blend of handwritten letters, drawing, collage, weirdness, and plausibility, all in service of depicting men in the process of achieving more authority and control. This and other works on the theme of power can be found in Deb Sokolow: Men at Western Exhibitions (September 17 – November 5, 2016).

In another work, “The Embarrassing Incident at the Kremlin” (2016), Sokolow recounts, in straightforward descriptive prose, an actual event that took place in March 2015, when President Putin hosted a group of women at the presidential palace in Moscow to celebrate International Woman’s Day. It seems none of the President’s aides informed the women to wear flats rather than high heels, because in official photographs, no one can appear taller than Putin, whose height is believed to be between 5’ 2” and 5’ 5”. As a result, they were instructed to bend their knees when they were photographed with the President. The kicker is Sokolow’s claim that the Kremlin later solved height differentials by installing an adjustable floor, which, if you think about the extent of Putin’s vanity, seems altogether believable, and which inevitably raises the question of how far a man with immense power might go to uphold his self-image. Sokolow adds a further note of absurdity by claiming that the former French Present Nicolas Sarkozy, who is officially 5’ 5”, “is brought in to advise Kremlin staff on possible solutions to avoid height compromising situations.”

What further endeared me to Sokolow’s work were the afterthoughts she adds to the text, usually in the margins, and the places where she whites-out and redoes the letters. In “The Embarrassing Incident at the Kremlin,” we read in the margin beside Sarkozy’s official height that we don’t know what his unofficial height is. Is he shorter than his official height? By some unlikely chance is he actually taller? How will we ever know? And is it really that important?

Sokolow’s interest in the well-known illusionist David Copperfield, who once made the Statue of Liberty briefly disappear, an act which purportedly interested Putin, reminds us that everything we see, especially in politics, may in fact be an illusion, a form of deception, a cover-up – all of which appeals to anyone who has ever entertained a conspiracy theory. For all the deadpan humor running through Sokolow’s work, along with a sharply attuned fascination with human foibles, one also senses her utter amazement: can people really be serious about these things? Are they really that important? If you find the answers disturbing, you are not alone.

The Ridiculous, The Real, The Amazing. A Review of Deb Sokolow at Western Exhibitions

New City

by Brit Barton

October 5, 2016RECOMMENDED

Deb Sokolow is up to her usual antics: creating witty, intricate and politically resonant artwork. As the title—simply “Men”—suggests, the subject is a collection of misters who all possess narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy, known collectively as the “dark triad.” By intersecting the factual matters and occasional fictions of those like Vladimir Putin, Frank Lloyd Wright and Donald Judd, the artist is at her forte, taking diabolical personalities and their mythologies to task through great humor and real anxiety.

With a variety of sly drafting and sculptural methods, Sokolow subverts the gaze these men are used to controlling. In examining their historical notoriety, they begin to slip into doubt and suspicion against the probable. For instance, some cursory fact-checking on Sokolow’s claims proves that Kim Jong-un is obsessed with Michael Jordan (not, necessarily Dennis Rodman), but had there really been plans to kidnap him? Maybe.

Beyond their provocative narratives, Sokolow’s drawings are precise and considered. Using a variety of minimalist-inspired linework, color fields and diagramming, her methods are also met with three-dimensional folds that give way to architectural renderings, further blurring the lines of the two-dimensional schema that conventional drawing often binds itself to. Her diagrams in particular are well within vernacular, creating a shifting navigational tool for her evidentiary aims.

After looking at the work, one has to wonder how society has let these men—full of narcissism and bravado—bend and shape history. The genius of Sokolow lies within the lens she has given us—all stories that are improbable, but as our current reality goes to show, quite possible. (Brit Barton)

Deb Sokolow’s thoughts on Men

New American Paintings

by Brad Fiore

2016Those unfamiliar with the work of Deb Sokolow (NAP #41, 107, 119) might be surprised to find studio walls plastered with images of Kim Jong-un, conspicuously undetailed renderings of David Copperfield’s brain, paper models of Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, as well as diagrams dissecting the psychological motivations of our country’s most notorious politicians. And over the past decade she has found excuses to cook up an impressive collection of home-brewed conspiracy theories that cover everything from subterranean pirate tunnels to coded messages in your McRib. Though while she has earned a reputation for drawing on eclectic source material, the most surprising thing about her work is its ability to synthesize all of it into something that’s not only visually cohesive, but as immediately compelling as anything in the National Enquirer.

Brad Fiore: I’m curious about what your process is looking like right now. In the past, you’ve drawn from books on conspiracy theories, casual and not-so-casual spying on your neighbors, and what I imagine amounts to lots of time writing-out square lettering. How have you been spending your time in the studio? What kinds of things are you thinking and reading about? Who are you spying on?

Deb Sokolow: I might be putting most of my cards on the table by admitting that I have not been keeping up with any spying whatsoever on anyone in recent months. That activity has been replaced by a total obsession with the current presidential campaign. So "studio time” for months has meant watching CNN and reading every single news story on the election.

Maybe it’s all so interesting to me because in another life I interned for a congressman on Capitol Hill. That gig opened my eyes to politics and a world abundantly populated with individuals, specifically men, who seem to exhibit one or more of what psychologists refers to as “the dark triad” personality traits: narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy. I’ve been reading Maria Konnikova’s recent book, The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It . . . Every Time, which provides a pretty fascinating analysis of these traits and why people are so drawn to individuals who exhibit them. I’ve also always been interested in male cult leaders, businessmen, drug lords, actors, artists and architects- not just politicians- who fall into this category. Certainly there are women who possess these traits, but it's the addition of copious amounts of machismo that makes it terrifying and ridiculous and ultimately more fascinating for me.

BF: What’s interesting about your work is how it often takes the form of political commentary, institutional critique, or social practice but then completely subverts them by leaning heavily into your own personal paranoias. Is your work apolitical and asocial or do you just have unique priorities?

DS: People and politics and institutional structures are so intensely strange and complicated, and while I love some political art and some examples of social practice and institutional critique, I find it hard to connect with it when it takes itself too seriously, when it presents just one side of a complex issue or when it pretends to be about something important but it doesn't really say anything at all. I don't know if what I'm making is political or apolitical, but I know I want to make something that someone would actually spend time with, and humor and paranoia are two devices I use to try to draw a viewer in.

BF: As far as political, social, or institutionally focused work that you love, are there any examples that come to mind?

DS: I'm always interested in what Fred Wilson does. At the Speed Museum in Louisville, I recently saw "Urban," a fascinating photo and text series on homemade urban structures by Marjetica Potrč. And I'm a huge fan of both William Powhida and Mark Lombardi's drawings.

BF: I’m wondering how much this exhibition is an evolution of, or a departure from, your previous works that circle around issues of gender dynamics. Are you still nurturing a romantic obsession with fictional boxers and how much do you think Rocky is like the men you are talking about in your new work?

DS: I might still have a small romantic obsession with the fictional boxer, Rocky (just the Rocky in the first movie, and not the Rocky in any of the sequels). But Rocky might be an outlier for me. There has always been this common thread throughout my work that focuses on men who, unlike Rocky, exhibit a combination of dark triad traits. About a decade ago, I made a series of drawings on the imagined mansion-estates of various drug lords, and in the last two years, I've been researching the dark side of Frank Lloyd Wright. The men featured in the Men show will most likely be unlike Rocky. But who knows? I might decide to insert Rocky in at the last minute.

BF: Anything else you want to tell us about the upcoming show at Western Exhibitions?

DS: This is where I'm at; this is what I'm thinking about. Dangerous men, devious men, unlikeable men with delusions of grandeur. This is what I've been researching for a series of drawings for the Western Exhibition show in September. I don't know what the final outcome will look like, since it's all currently in process, but it will most definitely be about men.

Politics, Smoke, and Mirrors–And Drawings. Deb Sokolow: Debate Stage Water Bottles at G Fine Art

Bmore Art

by Terence Hannum

June 6, 2016Considering that the stress of this political season hasn’t come close to a final curtain, an exhibition like Deb Sokolow’s Debate Stage Water Bottles at G Fine Art proves that truth is stranger than fiction.

For years, Sokolow has mined the territory of obscure minor histories, cinematic idiosyncracies, and total fiction in her visual output. Whether diagramming the hidden treasures beneath the city of Chicago placed there by the dynastic Daley family, or the illuminati-like apocrypha of the Denver Airport, her drawings of architectural spaces, snippets of historical dialogue, and snide asides form compelling, and often hilarious, narratives.

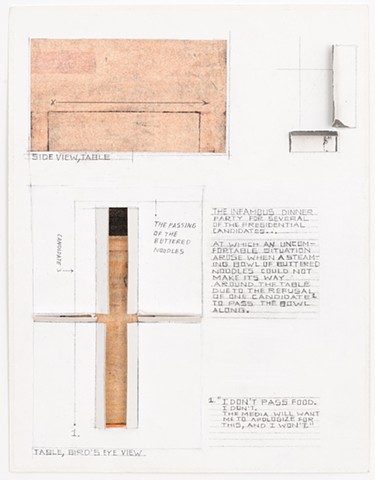

In Debate Stage Water Bottles these small drawings and relief collages walk the line between insider campaign diagrams and bizarre internal commentary from political figures. In addition to their content, Sokolow’s practice of highlighting changes or ‘mistakes’ gives them depth and makes them even more intriguing; each is full of erasures, white outs, and redrawing. This worn quality animates each piece, as if you’re catching a work just coming into form or seeing an excavation emerge. Many of these pieces also contain odd three-dimensional elements that come off of the page as flaps and berms to indicate stage directions, walls, and other formations.

For example in “Copperfield’s Sequence of Optics” we read about a stage plot to increase an unnamed candidate’s stature on stage. This is told mostly through crayon and colored pencil collaged on paper with relief walls of paper coming off of the page. There is a comment on the top right that reads: “1. Mostly Smoke and Mirrors 2. Both Mental and Physical.”

While we’re all in the throes of what is shaping up to be a horrible election season (and in reality, aren’t they all?) I cannot think of a more apt two lines, whether they’re about “millionaires and billionaires” or a “great big beautiful wall,” both imaginary and actual.

Many of these pieces, like “Carpet Patterns” appear from afar as sketches for hard-edge abstraction or architectural mapping. Carefully delineated rectangles from crayon, acrylic, and colored pencil belie the annotations. Many of these pieces read like a schematic, marked with arrows and conspiracy theories. There’s a level of compositional satisfaction that can be derived from just viewing them as pure drawing, but reading them as narrative fiction elevates them to a higher level.

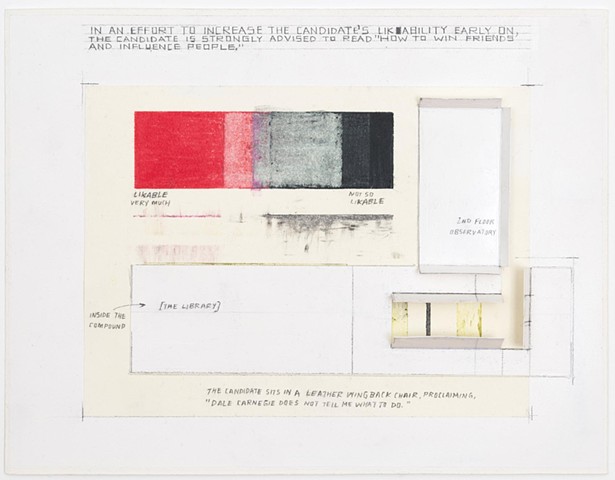

Sokolow’s fictions reflect specific and actual people whose egos have propelled them to the spotlight. None of these egos are explicitly stated, but it isn’t hard to extrapolate certain characteristics, for example the reckless bombast of Donald Trump (“The media will want me to apologize for this, and I won’t”) or the pathetic aura of Jeb Bush. Although there are no asides that spell out, “Please clap,” there’s a certain patina of the ill-equipped politician out of his depths represented throughout the exhibition.

These pieces resonate upon a narrow lens of reality they present through fictive construction; they’re funny but they also wound us. You don’t know who each politician is, but each description rings true.

In politics, and especially in America, we believe certain delusions about those we vote for, but we believe them of ourselves in equal measure. These are the foggy perceptions of truth, hope, ideology and in the end, personality – or the perception of what a personality is.

Deb Sokolow is adept in crafting and combining these tropes and expectations, revealing the artifice upon which our culture of political narratives is built. Through these revelations we can see the weak, shallow, and shaky foundations our modern representative democracy is founded upon. Although presented with humor, Sokolow’s drawings illustrate a pressing danger; how easily our system of governance can falter, because of inherently flawed voters and even more flawed political figures.

Deb Sokolow: Debate Stage Water Bottles

Washington Post

by Mark Jenkins

May 6, 2016They don’t feature massive noses or monumental comb-overs, but the drawings in Deb Sokolow’s “Debate Stage Water Bottles” are political cartoons. The Chicago artist renders slightly 3-D schematics of offices, auditoriums and “the McDonald’s on K St.,” decorated with washes of color and brief comments about campaign strategy. She imagines combat fought with “victorious carpet colors” and the “deliberate sabotaging” of the containers mentioned in the G Fine Art show’s title. One candidate displays resolve by refusing to pass food at dinner, vowing that “the media will want me to apologize for this, and I won’t.”

Because Sokolow doesn’t name names or portray faces, the rooms she defines with folded-paper outlines could be anywhere that people — well, mostly men — compete by guile rather than force. These white-collar arenas are timeless, yet somehow this seems to be the right season for the artist’s drollery.

When How It Looks Matters More Than What It Says: ‘Drawing Time, Reading Time’ at the Drawing Center

The New York Times

By Ken Johnson

November 21, 2013Asemic, elegantly calligraphic works in “Drawing Time, Reading Time” by Pavel Büchler, Mirtha Dermisache and Guy de Cointet are like scat singing, pure visual music. In a similar vein, Nina Papaconstantinou creates a kind of minimalist, visual drone by hand copying onto single sheets all the pages of whole books using blue carbon paper to transfer her handwriting. The illegible, dense field of fine blue marks of one piece represents the entire text of Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber.” While not asemic, typewritten works of concrete poetry from the 1960s by Carl Andre suggest a form of chanting.

Not to be confused with mystic or surrealistic automatic writing, which is supposed to tap into unconscious depths, asemic writing in art highlights the relationship between “the written word’s communicative transparency on the one hand and visual art’s material opacity on the other,” as the organizer of both exhibitions and the Drawing Center’s curator, Claire Gilman, puts it in her exhibition catalog essay. That in turn invites thought about the nature of meaning itself: Is it some kind of transcendental substance that may or may not be incarnated in some physical form? Is the relationship between meaning and material form like the relationship between your body and your soul?

For some artists in the show, verbal meaning apparently matters, but to what extent is hard to say. In 1993, Sean Landers hand wrote on 451 yellow legal pages an entertaining, autobiographical account of his trials and tribulations as an artist and a pursuer of sexual, romantic and other gratifications. It’s titled “[sic].” All the pages are here pinned up in order in a wall-filling grid. The installation makes it impossible to read the whole and renders uncertain exactly what “[sic]” is. Is it art or literature? Is it to be read, looked at or thought about?

A richer relationship between form and content animates Deb Sokolow’s series of poster-size drawings, “Chapter 13. Oswald and Your Cousin Irving.” Words rendered by large, neatly made letters as well as diagrams and photographic images tell a remarkable story about the assassination of John F. Kennedy and its aftermath. At the start, you learn that Ms. Sokolow had an older cousin who was a mentor to a teenage Lee Harvey Oswald. The drawings go on to ponder mysterious circumstances relating to the assassination, including that Mary Pinchot Meyer, a painter whose diary revealed trysts with Kennedy (she was part of a circle of artists and intellectuals who were exploring psychedelic drugs and orgone therapy), was murdered less than a year after Kennedy.

The eccentrically forensic style of Ms. Sokolow’s zany project reflects her effort to comprehend the facts and rumors, as if she herself were a justifiably paranoid character in a Thomas Pynchon novel.

The book as a physical object is the ostensible subject of carefully made, realistic pencil drawings by Allen Ruppersberg and Molly Springfield. Like everything else in both exhibitions, they are paradoxical: Writing is material, and, then again, it’s not. Made in the 1970s, Mr. Ruppersberg’s works represent books like Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal” and Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style” lying closed on undefined surfaces. What’s the relationship between what these volumes look like and what they contain?

Ms. Springfield’s drawings are from a 2007 series called “The World is Full of Objects,” whose title refers to the conceptualist Douglas Huebler’s famous statement, “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” From a distance, they appear to be a grad student’s smudgy, black-and-white photocopies from library books. Up close, you see that they are lovingly hand-drawn copies of photocopies of pages from books about conceptual art of the 1960s, including Lucy R. Lippard’s “Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object.”

What is an object, anyway? Must it be something material? Can a concept be an object? Are words and poems objects? What about sounds, actions and events? If an object exists only in a photograph, is it still an object? Do imaginary objects count? If you allow that a question can be an object, then such queries could be the primary objects of Ms. Springfield’s beautifully realized, brain-teasing drawings.

An Installation of Dirty Politics and Illusion: A Review of ‘Some Concerns About the Candidate,’ at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford

The New York Times

by Martha Schwendener

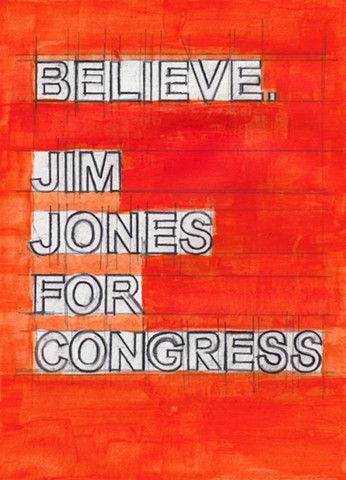

March 8, 2013In the simplest sense, Deb Sokolow’s “Some Concerns About the Candidate” at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford is a clever installation driven by a single conceit: a fictional narrative in which a Congressional candidate hires a campaign consultant to help him get elected. The protagonist, referred to throughout the exhibition as “you,” is a campaign worker who falls under the candidate’s spell — but ends up documenting an unfolding tale of intrigue and deceit.

There is a hook, however. Borrowing from postmodern authors who created fictional narratives using the names of historical individuals, Ms. Sokolow’s candidate is actually Jim Jones, the notorious cult figure and leader of the People’s Temple, whose followers drank cyanide-laced Flavor Aid in November 1978 (ushering in the concept of “drinking the Kool-Aid”); his campaign consultant is David Copperfield, the magician and illusionist who gained fame around the same time — and whose pseudonym was borrowed from the Charles Dickens novel “David Copperfield.”

The six panels that make up “Some Concerns About the Candidate” (2013) employ elements of collage, painting and pre-digital advertising paste-up. Handwritten texts scrawled onto the works describe the campaign worker’s journey. “Remember meeting Jim, when you were still working at the bookstore?” asks the first panel, dated Aug. 15 at the top. “He was holding a copy of ‘The Art of War’ and was staring at you, intensely: ‘You should do something meaningful with your life,’ he said, handing you a campaign flier.” The next day “you quit the bookstore” and went to work on his campaign.

On Sept. 2, according to the second panel, “Copperfield comes by campaign headquarters,” but “something about this doesn’t feel right.” Accompanying real-life photos of Mr. Copperfield are descriptions of the fictional campaign consultant’s underhanded strategies: infiltrating the opposing candidate’s rallies, sorting through office trash baskets for information and coercing campaign workers to perform “uninvited home entry.” (The campaign worker also finds herself making visits to Jim’s water bed.)

A panel dated Nov. 5 offers a local twist: according to the text in the work, the campaign headquarters have been moved to Hartford; a photo pasted into the work shows John F. Kennedy delivering a speech on the steps of the Hartford Times Building on Election Eve in 1960. Ms. Sokolow’s candidate is scheduled to do the same thing — but suddenly he disappears.

“On a hunch,” the panel tells us, the campaign worker searches the galleries of the Wadsworth and finds Jim standing in front of “Retroactive I” (1963), a painting by Robert Rauschenberg that features a silk-screened photograph of Kennedy. (The actual painting is currently on view in a nearby gallery.) But the candidate has gone delusional, muttering the words “I am Kennedy”; he has also dropped an index card describing “tactics for controlling the minds of others.”

So ends Ms. Sokolow’s absurdist political saga — although the show also includes ephemera like Mr. Copperfield’s brown vinyl briefcase and fragments cut from business suits that the campaign worker supposedly bought from thrift stores, chopped into pieces and handed out to adoring fans, claiming they were Jim’s suit-relics. There is also a grid of acrylic “Campaign Poster Designs Rejected by Jim Jones” (2013), with small handwritten notes providing a meta-commentary; the small print next to “Jim Jones/ The People’s Candidate for Congress,” reads, “Jim reminds you he’s not running for Congress in China.”

Ms. Sokolow’s exhibition is funny, smart and well researched, although there are moments when the comedy falls flat or the objects don’t carry their weight, like the plain briefcase displayed on a pedestal or a pendant with a hand-drawn image of Jim Jones displayed in a vitrine. She is also good at extending the boundaries of art to embrace comic books, graphic novels and posters, and tweaking site-specificity, which originated in sculptural installations tied to specific locations, into an ingenious (if slightly obvious) narrative device.

But Ms. Sokolow is clearly after bigger things. Is she implying that contemporary politicians are dangerous cult figures and their advisers master illusionists? Is she comparing art to propaganda (and vice versa)? In many ways, her work might follow in the lineage of artists like Jeffrey Vallance or Mark Lombardi, who tracked shadowy politics, hidden histories and what might be labeled conspiracy theories.

And yet, Ms. Sokolow is from a younger generation — one that leans toward the earnest and personal rather than the detached or cynical. There is comedy and wit and all the techniques of postmodernism, from parody and pastiche to high-absurdist irony. But there are also texts filtered throughout the works that head in a different direction.

“Where was your crisis of conscience when you were a willing participant in this?” one texts asks. It is written above a photo of hands waving in a crowd, anonymous, but clearly ecstatic. Here, critical detachment, that other hallmark of postmodernism, is clearly erased.

“Deb Sokolow: Matrix 166: Some Concerns About the Candidate” is at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 600 Main Street, Hartford, through June 30. Information: (860) 278-2670 or wadsworthatheneum.org.

Deb Sokolow: Abrons Art Center

Artforum.com

by Brian Droitcour

August 8, 2011Deb Sokolow’s Notes on Denver International Airport and the New World Order, 2011, has the makings of a paperback thriller you’d buy at an airport: a shadowy cabal of powerful men, a blue-collar crackpot who claimed to know their secret and died strangely, and an anonymous journalist who comes out of nowhere to supply the protagonist with a file of classified memos. The protagonist is Sokolow. But in her telling––written alongside diagrams, blueprints, photographs, and news clippings that are printed or taped on sheets of cheap copy paper––she becomes “you.” The use of the second-person pronoun evades the diaristic while sharing doubt with more immediacy.

In Sokolow’s work, the affect of uncertainty doesn’t stop at conspiracy theories about the “New World Order” and their meeting place under the Denver International Airport. A question about the tons of dirt removed from the airport at night expands to wonder about the secrecy of anything done under cover of darkness. Halfway through the parabola of panels, “you” travel to Denver to see what “you” can observe for yourself. But there’s no evidence besides suspicious activity. As “you” poke around, “you” are trailed by a truck, and by a Dairy Queen employee who roams an airport without a Dairy Queen. The last panel shows four chambers connected by a square of corridors, white against a black field. One chamber is black but smeared with correction fluid. Is this supposed to be part of the airport? The imagined bunker? You’re only certain that it’s an enlargement of an image from the first panel. But the close-up shows nothing new.

About half of the text was penciled in after the pictures were hung, and there are signs of second-guessing: words obscured by graphite squares, awkward enjambments. Any seasoned viewer knows that rough-edged spontaneity in works on paper implies intimacy, honesty, confession, or sometimes testament. And here it’s certainly a contrast to the televised flashiness that often spreads conspiracy theory. But Sokolow refreshes these clichés by circulating them among truth and secrecy on a global scale. Do you trust an artwork by Deb Sokolow more than a television show hosted by Jesse Ventura? Are her methods any less manipulative? Does she want to convince you of anything other than doubt?

www.artinamericamagazine.com

Production Site MCA Chicago

Art in America

By Janet Oh

May 25, 2010Production Site: The Artist's Studio Inside-Out reflects on the singularly tense position between projection and the real (that of both audience and artist) occupied by the artist's studio. The exhibition at the MCA Chicago includes the works of 13 artists and coincides with Studio Chicago, a year of programming spanning the city.

The exhibition begins with a select timeline of artists' renderings of the studio, in which the space appears as a metonymic portrait or self-portrait. A Rembrandt featuring the artist in his studio and a Stephen Shore photograph of Andy Warhol seated in The Factory, in particular, highlight the schism between authentic and personified portrayal that hinges on the myth of the artist.

A walk-through of this exhibition compares to a marathon of studio visits, as nearly every artist occupies one full room, which gives each installation a theatrical quality while playing down formal comparison. Justin Cooper adds a layer to this staged feeling by exploring the studio as a map and an index of the artist's brain. His video, Studio Visit (2007), addresses the anxiety associated with a visit from an outsider such as curator or critic. Shot to assume the perspective of an unseen creature attempting to draw a still life, the frantic and frustrated tone of the video culminates in an outburst of destructive havoc. Cooper's creature wheezes and pants, while the viewer considers the point at which both artwork and studio might be best socialized.

For his seven-channel video projection MAPPING THE STUDIO II with color shift, flip, flop & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage) All Action Edit (2001), Bruce Nauman left a video camera to record his absented studio at night. Little occurs, although occasionally a mouse, cat, or moth crosses the frame. The artist's belongings lie abandoned, glowing under steady infrared light. The screens gradually change color and the screens flip at uncoordinated time intervals, forcefully comparing the studio visit with surveillance such that the viewer must ask him or herself what they are looking for, exactly.

Deb Sokolow frames her treatment of her Chicago studio building as "the paranoid narrator" in You Tell People You're Working Really Hard On Things These Days (2010). In floor plans and written descriptions, she's depicted the police discovery of a methamphetamine laboratory, and sketched Richard Serra as a mobster. During the exhibition's run, Sokolow updates the drawing with events in her building, transposing studio to exhibition site. Paranoia, it seems, is no obstacle.

In three video works by William Kentridge, the artist alchemizes artistic procedure to cinematic technique. The seven-part live-action and animated suite, 7 Fragments for George Méliès (2003), sees the artist filming himself drawing in his studio. The edited footage plays forwards and backwards, breaking from a linear depiction of production. Kentridge tears up a self-portrait, which reverses into a mending gesture, and never has the anxiety of production seemed more like play.

artforum.com

Production Site: The Artist’s Studio Inside-Out

Artforum.com

By Claudine Ise

2010“Production Site” highlights the studio as a place of work, as well as a compelling aesthetic subject in itself. The “selected visual history of the artist’s studio”—installed on a wall directly outside the exhibition galleries, as an initial point of reference—includes a variety of iconic images: Jackson Pollock throwing his body into an “action” painting; Lee Bontecou in her New York studio, blowtorch in hand; Andy Warhol seated alone in his cavernous Factory. There’s even a film still of Julianne Moore as an “avant-garde feminist artist” from The Big Lebowski (1998).

This ancillary display reminds viewers that long-standing misperceptions about the nature of artists’ studios are inevitably linked to the clichés surrounding artists themselves. Perplexingly, however, it is also one of the few points in the exhibition where practitioners actually manifest an embodied presence. Mostly, they appear as trace elements: the whirling dervish of anxiety in Justin Cooper’s video Studio Visit, 2007; the hot white blob of infrared light shutting the studio door at night (Bruce Nauman, Mapping the Studio II, 2002); the covert operative who comes in to expand and edit her painting’s sprawling narrative only on Mondays, when the museum is closed (Deb Sokolow, You Tell People You’re Working Really Hard on Things These Days, 2010).

There are several memorable exceptions. Nikhil Chopra’s two-day gallery performance offered a brief but potent instance of an artist responding directly, if theatrically, to his immediate environment, while William Kentridge’s magnificent multichannel animation—a meditation on the medium’s place in the history of cinematic trickery—draws viewers into a space that feels authentically “magic,” despite all evidence to the contrary. It’s like walking into a waking dream.

articles.chicagotribune.com

A look inside the artist's studio

Chicago Tribune

By Lori Waxman

May 07, 2010Not much is happening in Bruce Nauman's studio. Hours go by. An insect flits. A mouse darts. A cat follows. Everywhere are scraps of this or that, a piece of furniture, a blank wall, a doorway.

Nauman has been thinking about what happens in the studio for a long time, since he first got one in the 1960s. Then as now, the end result of that thinking is an agonizing and witty bit of videotaped navel-gazing, a peek at that which confronts any artist upon opening the studio door: What am I going to do now?

If you're a conceptual artist, it might not look like much of anything — at least that's what Nauman seems to be suggesting in his six-screen, six-hour installation, which forms part of the Museum of Contemporary Art's smart, sprawling exhibition, "Production Site: The Artist's Studio Inside-Out."

Yes, conceptual artists maintain studios just like painters and sculptors and draftsmen. In fact, as the MCA's exhibition demonstrates, sometimes it's those more traditional artists whose studios function in less-than traditional ways. Take the two creators who treat the museum itself as a space for making art: the work presented by both Nikhil Chopra and Deb Sokolow can best be described as drawing. And yet there it is, happening live in the museum itself.

Chopra's two-day performance began with a mesmerizing turn in which the slight, Indian-born artist played Yog Raj Chitrakar, a fictional Victorian character in a loincloth who spent many trancelike hours covering the gallery's walls with evocative whirlwinds of charcoal. Visitors' shoes picked up the black dust that covered the floor, tracking it throughout the museum to make a secondary, temporary (and perhaps unintentional) picture.

Sokolow's charmingly paranoid mural-scale drawing diagrams various conspiratorial tales about the goings on in and around her studio building. According to the artist, these include but are not limited to a meth lab, suspicious Russians in room 501, and the "situation" in the parking lot across the street. On most days, Sokolow's piece hangs like any other, and says a lot about what the artist is doing in her studio when she's supposed to be "working" on art (she's spying on the neighbors). Once a week, however, Sokolow does what you are not supposed to do in a museum: she climbs up a scaffold and touches up her work, adding to this narrative, changing that one, starting another one entirely.

It's worth noting — and applauding — the fact that Sokolow, a local artist, has been given pride of place in the museum's atrium. The MCA has not been known for recognizing Chicago talent far beyond its 12 x 12 shows, but "Production Site" includes Sokolow plus John Neff, Justin Cooper, former Chicagoan Amanda Ross Ho and Kerry James Marshall. No surprise on the latter, perhaps, but a welcome change overall, and one the MCA will hopefully repeat.

Ross Ho offers a particularly literal take on the idea of the artist's studio, presenting the actual walls of her Los Angeles workspace as the work itself. This might sound dull, but it is only if you lack the imagination and willingness to follow the subtle clues Ross Ho has left behind.

A Notorious B.I.G. poster, a wee balloon sculpture, a Chinese New Year mask, mismatched jewelry, paint drips and more suggest a diversity of work come and gone. Admittedly, this envisioning process is substantially easier for viewers already familiar with her work, but it might just be more fun for others.

Peter Fischli and David Weiss seem to have done something similar to Ross Ho, transporting not the walls but the messy contents of their studio into the gallery. But look again (or read the materials list and then look again) and discover that their project has nothing literal about it. Instead it is a confoundingly realist recreation of a studio from carved and painted polyurethane — a fake studio for a fake artist, presumably made in some kind of real studio by real artists, about whom we learn little.

The very opposite is the case with Andrea Zittel, who installs wood furniture, felted organizers and other designs from the desert home-cum-studio in which she makes and tests her customized goods. Through her products, slogans and a documentary, Zittel promotes a lifestyle as ostensibly simplified, empowered and handmade as her own — though in its insistence on limits and its focus on material objects, her program often seems more fascistic than liberating.

Plenty of other artists in the show focus on the studio as subject, including Rodney Graham, Ryan Gander and Tacita Dean. None of them, however, seem to be taking as much playful pleasure as William Kentridge does in his own workspace, where he animates the universe in charcoal, spilled coffee, ants and sugar. Kentridge's witty, self-reflective twist is to film himself in the midst of that universe, bumbling amicably amid flying sheets of paper and pictures of himself. The result is a portrait of the artist in the studio, a studio at once traditional and contemporary, a studio that shares with the viewer much of the wonder it contains. Would that all artists' studios — and artists — produced such generous, captivating meditations on the world.

art.newcity.com

Review: Second Stories—Artists Making Do & Fixing Up/Zolla Lieberman Gallery

New City

by Abraham Ritchie

June 2009Disaster, whether natural or human-made, is at the heart of the large group exhibition “Second Stories.” Curators Brian Gillham and Rachel Kalom bring together artists working in a variety of media that generally reflect America’s newfound frugality, hence oil on canvas takes a backseat to work made from materials such as cardboard, packing tape and found objects. Taking satirical aim at luxuries and commodities (including art), Vijay Paniker’s ceramics update wine and cheese parties for the current recession: a tube of easy cheese and a box of wine. We’re not giving up these luxuries; we’re just giving up good taste.

Deb Sokolow’s work panders to fear-mongering. Her “CIA Failed Assassination Attempt #3” recounts one of the CIA’s unsuccessful attempts at assassinating Fidel Castro by paying $150,000 to an agent of the Mob to arrange the hit. She humorously concludes, “The CIA should’ve gotten their money back on this one.” Sokolow combines obvious cover-ups, effacing and slightly menacing dark shapes to convey both what we don’t know and the little we do about what the CIA exactly does or has done.

Though some of the work on view in “Second Stories” is passable, the art brought together reflects our current uncertainty, but as Paniker indicates, we’re not really that worried.

www.chicagotribune.com

Gallery winners from Sokolow, Harrison

Chicago Tribune

by Lauren Viera

May 29, 2009We warned you about local artist Deb Sokolow in 2008 as part of On the Town's "Ones to watch" roundup. If you haven't yet sought her out, here's another bee in your bonnet.

The artist's latest diagrammatic wonder, "The way in which things operate," signifies the debut of the Spertus Museum's new Ground Level Projects series (launched last month), for which four artists were commissioned to create works that will eventually live in the museum's growing contemporary collection. Before the new additions make their way to the Spertus Institute's top-floor museum, they're displayed for a spell in the ground-floor lobby.

Though Ground Level Projects is an awkward exhibition space -- the revolving door traffic and security desk provide constant interruption -- Sokolow's work is so absorbing, distractions are moot. "The way in which things operate" keeps in line with the 2004 Art Institute graduate's signature style: large scale, unpolished graphite-and-ink illustrated flowcharts detailing and dissecting mysterious predicaments, which may or may not be figments of the paranoid protagonist's imagination.

Like all of Sokolow's works, "The way in which things operate" starts out simple: "You" (the artist's recurring character) have a "problem." The culprit? A phantom Venn diagram.

Stay with me: As Sokolow so eloquently illustrates, "This 3-circled thing starts showing up in your dreams at night," until the protagonist succumbs to sleepless nights eating salami sandwiches over back-issues of Cat Fancy. Believable, non? The mystery follows Sokolow's shaky block lettering from her Division Street apartment building downtown to Manny's Deli for conversations with Robert De Niro about corned-beef sandwiches. Along the way, there's a stop at -- where else? -- the Spertus Museum.

Sokolow's pieces are less art than two-dimensional storytelling, and yet they're aesthetically fascinating -- eraser marks, correction fluid and all. Here's hoping "The way in which things operate" resides on a big wall in the museum once it graduates from ground level.

Deb Sokolow, "The way in which things operate" at Spertus Museum, 610 S. Michigan Ave., 312-322-1700, spertus.edu. Through July 19.

chicago.modernluxury.com

Studio 312

CS magazine

By Jaime Calder

February 15, 2010This month, Chicagoans will have the opportunity to decide for themselves when Production Site: The Artist’s Studio Inside-Out, an ambitious exhibition featuring work from a variety of artists, opens at the Museum of Contemporary Art. The works that comprise Production Site include photos, video, multi-day performances, sprawling installations and life-sized reproductions of artists’ studios, establishing these spaces in real time while simultaneously capitalizing on the sensationalism and mysticism associated with these workrooms.

“My first understanding of artists’ studios was based not on visits to actual spaces, but on what I gleaned from films like Scorsese’s New York Stories,” says MCA curator Dominic Molon. “A crossroad of experimentation and parties blown to mythic proportions by media and imagination—some artists have appropriated this wild image of socializing and partying, but for many the studio is a place of business.”

A mix of both new and existing works, Production Site invokes the studio space, paradoxically staging developmental spaces within the confines of the museum. Art star and Chicago resident Deb Sokolow, famed for her humorously sprawling story lines and incorporation of local topics, has been commissioned to create a large-scale floor plan of her studio detailing semi-factual activity within the space and surrounding neighborhood. This evolving installation, stationed on the MCA’s front lobby wall, will begin this month and continue developing throughout the duration of the show.

Other Chicago artists represented in Production Site include John Neff, MacArthur genius grant recipient Kerry James Marshall and former Chicagoan Amanda Ross-Ho, who cut up the walls of her old studio to use them as not only sculptural material, but also as a collage of her previous works, pictorially documenting her past creations through the remnants and splatters on her former space’s walls.

Equally exciting but drastically different is the two-day performance of Indian artist Nikhil Chopra, who will take on the characters of various artists and draftsmen from the 19th century, creating a living gallery space while audiences watch. Chopra’s elaborate transformations incorporate any number of costumes and props, all of which will be left within the space following his performance’s conclusion, creating a tangible record of his presence.

In a time when cell phones and laptops are taking the place of these essential spaces, Molon hopes Production Site will offer audiences a layered, realistic understanding of what studios actually are and how they function in a pragmatic way. Pragmatic? Well, maybe. Quixotic? Definitely. Between multi-channel video projections and photographic light-boxes, the realism of the studio is muddled as it is transformed into its own artistic entity. The end result, however, is phenomenal and grand in size. If, as one London journalist said, the studio is truly a reflection of an artist, then Production Site will surely take audiences through the looking glass.

art.newcity.com

Review: Deb Sokolow/Spertus Museum

New City

by Jaime Calder

April 2009Imagine you are being haunted in your dreams. The ghost is probably one of your relatives—specifically, one of your older, male, Jewish relatives–and he is trying to tell you something you don’t entirely understand.

Thus begins the meandering story of Deb Sokolow’s new work, “The ways in which things operate,” the first of a series of Ground Level Projects at the Spertus Museum. Sokolow, whose family keeps their archives at the Spertus’ Asher Library, combines her personal history with Chicago’s Jewish history though a hand-written, hand-drawn storyboard bursting with tangents, half-truths and occasional drawings of Robert De Niro. Spanning the walls of the Spertus’ street-level vestibule, the piece incorporates the museum in both the telling of the story and how the reader experiences it, guiding them by way of thinly inked arrows through the museum’s permanent collections, their hallways, and even down the elevators as it spins a half-true, half-farcical tale of family, life and loss in the Windy City.

Told in second person, this garrulous mural propels itself forward through the simple supposition that there is something from the past will change your life today. Sokolow’s ability to ensnare readers in her narrative is remarkable, drawing them in by the traced sketches and penciled commentary. The foundation of our past is an intoxicating subject for both Jews and Gentiles, and Sokolow successfully carries her audience through to the end of her story–an end that, at the time of this writing, has not yet been revealed.

http://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/story/520061.html

Kemper mystery exhibit is a you-dunit

Kansas City Star

by Alice Thorson

March 2008Chicago artist Deb Sokolow describes her elaborate wall drawing at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art as “one big cliché of a mystery detective story.”

But Sokolow’s story, titled “You Are One Step Closer to Learning the Truth,” is far more ambitious than your average whodunit. For starters, it covers all four walls of the museum’s meeting room.

Threaded with social commentary, existential angst, wry reflections on human behavior and a playful sense of the absurd, her energetic outpouring of hand-painted images and hand-printed texts offers a grand psycho-romp through American culture — with Kansas City as a staging area and the reader as protagonist.

“You are about to read a story,” states the opening line of text. “You are the main character.” That character is a hapless detective who receives a note from a woman named Mrs. Vincheslaus requesting help in finding her missing husband.

Dr. Vincheslaus is a “hermetic chemist” in the process of inventing a special KC-style barbecue sauce “with youth-enhancing results.”

A bit of detection, involving the requisite questions about his appearance and possible enemies (as well as his favorite foods and colors), yields the conclusion that the doctor has managed to find the mythic fountain of youth and that to find him, the detective must find the fountain.

Nothing about this story is straightforward.

For one thing, Sokolow constantly appends the main narrative with little tongue-in-cheek asides from the detective’s kvetching alter-ego.

“You’re in control of the story,” the artist informs the reader at the outset.

And then the little alter ego weighs in: “Wouldn’t it be nice to be in control of something just once?”

“But who are you?” the artist continues.

“Sometimes you’re not really sure who you are,” the inner voice observes with a hint of smugness.

The texts are enlivened throughout by visual accompaniments, including a bar graph assessing detective skills ranging from “The Best in the Field” to “As Good as Columbo.” An illustration of the spooky-looking exterior of the Vincheslaus house is followed by a Clue-style diagram of the interior.

Moving from one wall to the next, Sokolow cleverly incorporates the meeting room’s utilitarian features — a surveillance camera, a pair of emergency doors — into the story.

Shortly after the narrative gets going, it splits, inspired by the popular “Choose Your Own Adventure” series of children’s books that offer readers optional story lines.

In Sokolow’s tale, the story divides when the reader/detective must decide whether the fountain of youth is more likely to be found in Portland, Ore., or Kansas City.

Much of the fun of the story derives from its inclusion of familiar Kansas City locales, including the Raphael Hotel, Halls department store and Oklahoma Joe’s.

The worlds of pop culture and celebrity surface through appearances by Robert De Niro — cast in the role of a suspicious character who crops up at various points in the story — and David Copperfield, whom the narrative exposes as a fraud.

At one point, the detective considers what Ted Koppel, Oliver Stone and Nancy Drew would do in his situation.

Things get manic in all three lines of investigation. The Koppel-style inquiry leads to an encounter with a famous food critic. He believes that Dr. Vincheslaus is “adding kooky chemicals to food” that give people cancer, but worse, make the food taste bad.

The Oliver Stone story line takes a delightfully gory turn that explains “Why Kansas City barbecue sauce tastes so good.”

Alternative endings include an adventure in Kansas City’s Subtropolis caves with a reference to the museum’s recent acquisition of a 2006 painting of the site by Lisa Sanditz.

Through all these twists and turns, the narrator’s paranoia is a source of great amusement. Yet considered as a parallel reality to our own, the story’s not so funny.

In a media-saturated world where the lines between truth and fiction are often blurred, a little paranoia may be a sign of sanity.

http://blogs.jsonline.com/artcity/archive/2008/02/14/miranda-july-meets-mark-lombardi.aspx

Miranda July meets Mark Lombardi

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

By Mary Louise Schumacher

Feb. 2008Like the Choose Your Own Adventure children's books, Deb Sokolow's installation at Inova, "The Trouble with People You Don't Know," puts us into the role of the protagonist and invites us to make choices that determine how a plot unfolds.

Instead of turning pages, though, we follow arrows around the room. We walk ahead, turn a corner or linger in order to make choices in this story about the internal workplace dramas of a giant bookstore chain where we are a self-conscious staffer with a love of art books and Nancy Drew.

Will we fill out the application for the better paying, $22,000-a-year job? Will we go home and practice re-shelving books? Will we out our colleague who has just got to be dealing meth? Will we indulge our curiosity about the history of epidemics?

Setting the pace and direction of the story, driven by text and fashioned from basic "office" materials, like notebook paper and cardboard, is a bit like slipping down one of the Internet's many rabbit holes or like a spontaneous unfolding of the imagination. Except, we are not so in control.

The odd, fictional inner voice that drives the piece is Chicago-based Sokolow's creation. The uninhibited, paranoia-infused, sometimes obsessive and precise self-talk we're given, on loan, is a strange cross between performance artist-filmmaker Miranda July and the late, brilliant, conspiracy theorist-artist Mark Lombardi.

Inner arguments, printed out carefully in black and red pencil, become convincingly our own because they're open to interpretation. That they're also suggestive of an odd and distracted mind is something we put up with because the journey is so entertaining, because we want to know what'll happen next.

As we experience this fictional inner voice in tandem with our own, reacting to it, the artwork maps out something about our own habits of mind, about our distractedness, about our entertainment appetites and about how we navigate the layers of media, information and experience that are part of our lives.

Sokolow's piece is part of a larger exhibit of drawings curated by Nicholas Frank. Outside of the Milwaukee Art Museum, Frank does what few other curators do here: He explores a larger art world trend, namely large-scale drawing, through a specific strain within it, in this case drawings with a narrative aspect.

Deb Sokolow's "The Trouble with People You Don't Know" is on view at Inova, 2155 N. Prospect Ave., through March 14. Other artists in the show include Dominic McGill, Robyn O'Neil, Claire Pentecost and Amy Ruffo.

www.expressmilwaukee.com/article-775-pictorial-paranoia.html

Pictorial Paranoia

Express Milwaukee

by Aisha Motlani

Feb. 2008No wonder paranoids flourish,” says Nicholas Frank in his curatorial statement for “The Flight of Fake Tears,” a new exhibit at Inova/Kenilworth Gallery. He describes the void, the blank page, the unaccountable matter ingrained in our very existence, as the seat of a primal anxiety. Whether its through a tantalizing series of what-ifs or a feverish web of conspiracies, the work of at least two of the artists in the exhibit examines the means by which we repel the paralyzing uncertainty underlying human endeavor.

In The Trouble With People You Don’t Know, Deb Sokolow constructs an imaginary persona whose decisions the viewer has the power to direct. Pinned to the wall are a series of hastily scribbled drawings and notes, resembling an obsessive crime investigator’s cache of maps and photos, and outlining the range of possibilities open to this fictional character.

We read the pros and cons of each, commentary riddled with irony and selfdoubt, as we grope along the walls to divine the outcome of our choices. Dominic McGill’s Orchestra of Fear consists of a tent inscribed with livid headlines, epithets and irreverent caricatures. They look like the obsessive scrawlings of a madman, a media harlot and a keen social critic all rolled into one. Most unsettling is its air of disrepute. It resembles the kind of ominous abode that fairy-tale protagonists are cautioned to avoid but to which they’re irresistibly drawn. There’s even a drawing of a wolf in sheep’s clothing—or rather scout’s clothing—to strengthen this impression.

Yet Sokolow and McGill both place a curious distance between themselves and the persona around whom their work revolves. It’s not Sokolow’s thoughts we’re sharing in her piece, but those of a stranger racked by doubts and hopes which are no less crippling for being rather ordinary. The tent McGill constructs belongs not to him but to an imaginary recluse dwelling on the social periphery, out of sight but not out of mind.

Any creative act proposes a direct challenge to infernal and terrifying blankness. That aside, it’s still difficult to ascertain exactly how the work of Amy Ruffo and Robyn O’Neil corresponds with this idea of pictorial paranoia .

Ruffo’ s spare-looking drawings, with the almost sacred significance they place on the precise weight and quality of pencil lines, and O’Neil’s painfully detailed landscapes are self-contained pieces that seem utterly removed from McGill and Sokolow’s fretful meanderings. Perhaps the inclusion of Claire Pentecost’s work, which somewhat straddles both approaches, is an attempt to lend coherence to the exhibit. She draws on the walls of her studio, then photographs her work. The drawings represent a spontaneous act, mapping out an inner landscape that morphs and evolves. The camera lens arrests the evolution of the work and more importantly introduces an analytical distance between the artist and her creation. We don’t see the result of the creative act itself, but see visual evidence of it. Like Sokolow and McGill, Pentecost’s effort represents a self-conscious attempt by the artist to stand back from her work and view it through the dispassionate gaze of a stranger.

www.chicagomag.com/Chicago-Magazine/April-2007/After-Pashke/

After Paschke

Chicago Magazine, April 2007

By Joanna Topor Mackenzie

(excerpt)We polled gallerists and experts to find out which rising art stars we should be collecting now...

A few years ago, Deb Sokolow dumped her boyfriend for Rocky Balboa. "Rocky began to take the place of my own love story, because it was so much better," says Sokolow, 32. The result was a nine-foot-long, text-heavy, idiosyncratic cartoon that featured Sokolow herself as an alternative love interest for the boxer. Since then she has also dumped an unfulfilling sculpture-based studio practice and pursued her unique form of large-format diagramming-meets-storytelling. Sokolow's stories are almost always told by a paranoid narrator who is fascinated by the nefarious goings-on in the world. Subjects ripped from the headlines and whimsical themes like a pirate invasion of Chicago (Someone Tell Mayor Daley the Pirates Are Coming, now in the collection of the MCA) pepper her larger-than-life charts. Recent Hollywood interest in her work has fueled her exploration of the overlap between actors and the characters they play. "There's this sort of confusion about who celebrities really are, and I love that."

www.artnet.com/magazineus/reviews/orden/orden1-24-07.asp

The Windy Apple

Artnet, Jan. 2007

by Abraham Orden

(excerpt)At 40000, which founder Britton Bertran recently moved to the city’s West Loop gallery district, the artist Deb Sokolow -- another Chicagoan -- has installed a sprawling text and image piece titled Secrets and Lies and More Lies. Cute and nothing else, this work is a choose-your-own-adventure-style narrative that wraps around the gallery walls. The tale of intrigue takes place at the Winchester Mystery House in California, and the story unfolds in a style that is a blend of New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast and novelist Thomas Pynchon circa The Crying of Lot 49.

As a work of art, Secrets is remarkable in its total lack of pretension. The modest materials -- cheap paper, pencil, pen and acrylic paint -- connote a sort of planned obsolescence, a willingness to decompose, to not stand the test of time. Likewise the narrative form, which is often addressed to "you," making the reader the hero of the tale, seems to speak person-to-person, making the reader forget he or she is part of the public and thus eliminating the distance which that knowledge engenders.

Partially because of this quality, and partially because the piece falls short in certain regards (the story it tells is in no way unconventional), the work seems undeveloped or like a prototype that may or may not ever make it to the assembly line. This order of experience seems to be less and less available to today’s gallery-goer, so get it while you can.

www.newcitychicago.com/chicago/6016.html

Portrait of the Artist: Deb Sokolow

New City, Dec. 19, 2006

by Jason FoumbergDeb Sokolow, a 32-year-old artist from California who lives and works in Chicago, combines text and image in storyboards that unfold left to right through space. These diagrams chart both a narrator's inner-dialogue and external events that encompass both personal and political fictions. Sokolow began experimenting with flow-charts during her studies in The School of the Art Institute of Chicago's progressive Fiber and Material Studies program. Since graduating in 2004, she has gained widespread attention in many of Chicago's alternative and institutional art venues. Sokolow's art, like a serial pulp novella, has a definite appeal; Chicago viewers just can't seem to get enough. Her exhibition history includes the coveted 12x12 emerging-artist showcase at the MCA and a performance in a Marshall Field's window display.

Bred from her parents' library of political history and popular espionage novels, Sokolow's art is a tangle of myth and reality. Her current work at Gallery 40000, titled "Secrets and Lies and More Lies," presents Sokolow's experience of a ghost sighting at the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, California. The plot unfolds to include a possible terrorist scheme told through trifling details about the narrator. This narrator in Sokolow's drama--who is a consistent character in all her projects--is a bored and disaffected corporate-world peon who is officially in charge of ordering office supplies and unofficially in charge of guarding those supplies from theft. Such paranoiac tendencies breed further anxieties about the world at large. The narrator's voice is a reflection of insecurities about mediocrity, manifesting itself as a schizoid internal dialogue, an excessive use of correction fluid, the inequities of local politics, even a spooky house.

The narrator is only called "You," as in you, the viewer. "You" daydream yourself out of the city of cubicles and into a labyrinthine story of secret operations. The monotony and alienation of office life is transcended through a narrative that results in investigations into the bureaucracy of social relations in the information age. Fantasy spawns truth; whether personal truths or capital "T" Truth--both are the compound result of the humor and the horror of self-consciousness.

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4155/is_20060713/ai_n16545791/pg_2

On paper, MCA show is a smash

The Chicago Sun-Times, July 13, 2006

by Kevin Nance

Sun-Times art and architecture critic

(excerpt)Equally obsessive and absorbing, if with a decidedly lighter touch, is Deb Sokolow's "Someone Tell Mayor Daley, the Pirates Are Coming," which was seen last year at MCA as part of the museum's increasingly invaluable 12 x 12 series featuring younger local artists. This nervy piece, another super-wide scroll (this one marked up in ink, graphite and corrective fluid), is a high-concept hoot -- the first work of art to make me laugh out loud since Aernout Mik's "Refraction" video at MCA last year.

Sokolow's elaborate story line is that of a conspiracy theorist convinced that a band of pirates is coming to infiltrate and eventually plunder the Windy City. We're not talking about corporate raiders here; we're talking about the real thing, bloodthirsty vulgarians with eyepatches, peg legs and scraggly beards. (Think Johnny Depp.) They're digging tunnels, infiltrating the power structure, setting up meth labs (meth labs?), all in preparation for the day they appear in their warships on Lake Michigan.

What would Ted Koppel do? So the narrator wonders, before finally deciding to warn Mayor Daley -- but wait! What treasure is it, really, that the pirates are after? What if the first Mayor Daley secretly buried it on Northerly Island? What if his son tried to recover it by shutting down Meigs Field, guiding the backhoes by marking the spot with a giant X? What if . . .?

The answers can be found only at 220 E. Chicago.

www.chicagotribune.com

Putting post-9/11 fear on the map: Sokolow's dark vision at the MCA

The Chicago Tribune, August 19, 2005

By Alan G. Artner

Tribune art criticDeb Sokolow's immense new drawing at the Museum of Contemporary Art has the title "Someone Tell Mayor Daley, the Pirates are Coming," and not least because the artist staged a live-action version in a store window on State Street, there is the temptation to take it as James M. Barrie-like whimsy.

But the piece, which crosses various diagrams with a treasure map, is a good deal darker than that, thanks to its central character, a sleepless paranoiac whom Sokolow gives a soliloquy that nicely establishes a tone of post-9/11 hysteria.

The character's stream of consciousness unfolds on a single bluish sheet that covers parts of three walls in a gallery. Sokolow prints in various colors, illustrating aspects of the narrative while driving viewers along with dotted lines and arrows. An apparent street person sets everything in motion by screaming something that the narrator fantastically embellishes into an open-ended saga of old and new Chicago.

The wonder of it is less the quality of Sokolow's drawing than her effectiveness in creating a character and sustaining tension. Just like horror films transform fears that are already in the culture, so does this piece take our uneasiness about terrorism and recast it in the terms of a children's storybook that retains a very real urban anxiety.

For much of the last century narrative art was ridiculed. Literature and theater were supposed to tell stories better. Sokolow challenges that, and takes us along with her.

www.chicagotribune.com

Pirates invade Chicago

The Chicago Tribune, July 28, 2005

By Charles Storch"Someone Tell Mayor Daley, the Pirates are Coming."

As if Hizzoner didn't know.

Actually, it's not a cry about subpoena-carrying feds or GOP bounty hunters at City Hall's door but the title of a new work to be unveiled Aug. 5 at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Chicago artist Deb Sokolow, 31, said Wednesday that she hasn't finished the piece--a 48-foot, fantastical map of the city. She said it will include the text of a paranoid narrator certain that invading pirates will plunder a mayoral treasure--buried not in, say, the Procurement Services Department or Office of Intergovernmental Affairs, but at the former Meigs Field.

Sokolow's aware of the heat on City Hall these days but said: "I definitely have no intention of disparaging the mayor. This is a comical work of fiction. I hope he gets a laugh out of it."

www.chicagotribune.com

Review of Early Adopters, curated by Adelheid Mers at The 3Arts Club

The Chicago Tribune, October 21, 2005

By Alan G. Artner

Tribune art critic

(excerpt)Deb Sokolow's narrative drawings about a critic who disappears has the widest appeal. As she did in a recent show at the Museum of Contemporary Art, she tells (and illustrates) a story with the apparent innocence of children's books and old-time movie serials. This plays more engagingly than anything else on view, yet it's decidedly personal, not merely crowd-pleasing.